I grew up with a mother who hated women. All women, including herself.

Eventually, of course, that included me.

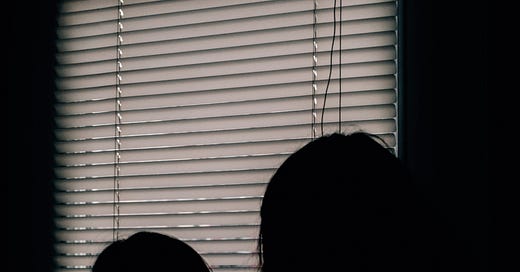

I learned this pretty early on, although as a kid I didn’t have the words for it. It was more of a feeling, this constant, unsettled knowledge that lived in my chest and my stomach that I was always on the cusp of doing something wrong. That I probably had done something wrong and just hadn’t been caught yet. That the default for me, as a female and the oldest sibling, was the expectation of a perfection that remained undefined—and defined or not, could never be achieved.

Of course, it had nothing to do with me, although I’m just now learning this. It had everything to do with how she was taught to look at herself.

It came out in the ways she spoke about herself.

It came out in the ways she spoke about other women (not highly).

It came out in the ways she looked at me, talked to me, interacted with me—which were vastly different than how she looked at, talked to and interacted with my brother.

The first time I really internalized it, I was 11.

My grandmother, who certainly passed this down to my mother, had taken me shopping and bought me a pair of jeans that I loved. One leg was white and the other yellow, and they made me super happy. When I got home and showed them to my mother, she made me try them on for her. Then she declared they had to be returned.

They were too tight, she said. And nice girls don’t wear things like that. The insinuation, of course, was that if I wanted to wear them I was not a nice girl. And since I fought her on returning them, it reinforced this idea that she had to save me from myself, whether I wanted to be saved or not.

The war had started.

This seems important to talk about right now, in the wake of the election. It seems important to really dig deep into what makes women hate ourselves so much that we’re willing to give away our power, our agency, our ability to think on our own.

It IS important to recognize whether we are afflicted with any deep-seated biases against ourselves. Because only in recognizing can we start to overcome them.

The tragedy of my mother is that she never got to the recognition phase of the program. She never saw that her way of thinking, of seeing the world, was not doing her any favors. I’m a hundred percent sure that to this day she doesn’t even know she hates herself, or that that’s what she was taught in her Catholic, conservative upbringing.

My mother is a highly educated woman with a Master’s degree and a teaching career until she retired. Yet ability to think strategically, logically, empathetically—meaning outside of certain sound bites or religious dogma—was never activated.

Her lack of self-esteem and self-worth was evident in the mantras she used, each one affirming some area of her life where she was lacking, not good enough, or not even worthy of making an effort.

Directed at herself, this thinking was tragic. But foisted upon her only daughter and blasted out into the world—well, that was harmful.

So how do women wind up in this predicament?

Professor Berit “Brit” Brogaard wrote about misogynistic women and the idea that there are four types. The one that stood out to me as most closely related to my mother’s way of thinking was The Puritan. This is how she describes her:

“Like the hateful male misogynist, The Puritan regards the ideal woman as thin, trim, youthful, pretty, alluring, mild-tempered, nurturing, compassionate, non-promiscuous, not too ambitious, ladylike in manners and presentation, and sometimes also as domestic and subservient to men… What makes The Puritan a misogynist is not her support of the feminine ideal but her hatred of women who purposely distance themselves from conventional femininity and traditional gender norms, such as feminists, career women and working moms. She targets these kinds of women because they are, in her opinion, bad women who willfully or recklessly offend against the natural order of things.” 1

To take it one step further I would add that in my mother’s case, her puritanical upbringing and the reinforcement of that through her fanatical belief in the Catholic teachings taught her that women are sinful beings who tempt men in all sorts of ways. And if you give in to that “sin,” well, you’re a lost soul who needs to saved.

And as Taylor Swift sings in But Daddy I Love Him, "I just learned these people try and save you... cause they hate you.”

So of course it makes sense that with Christian fundamentalism being so loud right now that we’re seeing this openly manifest in so many ways. These ideas about women being subservient beings who are only here to procreate has been at the center of political discourses over these last years, to the point where we’ve seen our bodily autonomy consistently being stripped away. And So. Many. Women. have nothing to say about it—or worse, are supporting it.

My mother is one of them. It hurts my heart to know she continues to harbor this deep, insidious hatred of herself, me, and so many other women out there whom she doesn’t even know.

I don’t know if we can help other women see that they are worthy as they are. That their worth doesn’t rely on how many kids they have, how many sexual partners they’ve had, if they love another woman, if they want a career over a family. That they are just as worthy as any man to have all the rights, privileges and self-worth that come so easily to men.

I do know that we have to look—really look—at ourselves to see if there’s even a shred of that self-hatred hiding under some judgment or belief we are holding close, then extract it. And burn it.

We deserve better.

Ooh, girl! Lots to unpack here. Thank you for sharing this.

Hindsight has shown me how, especially in those authoritarian areas, women tend to serve as the enforcers for the patriarchy. Their tools include ...

Gossip. Shunning (and I've never lived among the Amish). "Act like a lady." "You'd should fix up more." "Boys don't like smart girls."